I’ve been lucky. I’ve fly fished all over the world, from Alaska to the Zambezi. I’ve targeted everything, from the humble chub of my local River Cam in England to the arapaima of the Brazilian jungle.

I still fish for EVERYTHING with a childish enthusiasm, and my fishing friends will tell you that I have to be dragged away from the river – any river – when it’s time to reel up and head for home.

I love to fish for anything that swims. But for reasons that I struggle to explain, Atlantic salmon still draw me back again and again.

Why?

While the permit of the Caribbean flats or the big trophy trout of New Zealand offer a stimulating sight-fishing challenge of stealth and guile, let’s face it: Most salmon fishing is, to a great extent, an exercise in dumb luck.

Atlantic salmon fishing is mostly blind fishing for a quarry that are not duped into taking a cunning representation of their prey but that simply grab the fly out of curiosity or irritation.

There are also bigger, meaner fish out there. The monster tarpon of the Nicaraguan jungle, the blistering powerhouse giant trevally of the Amirantes, or the cartwheeling sailfish that sizzle into the blue skies above the Pacific are all undeniably bigger and stronger than even the most titanic Atlantic salmon.

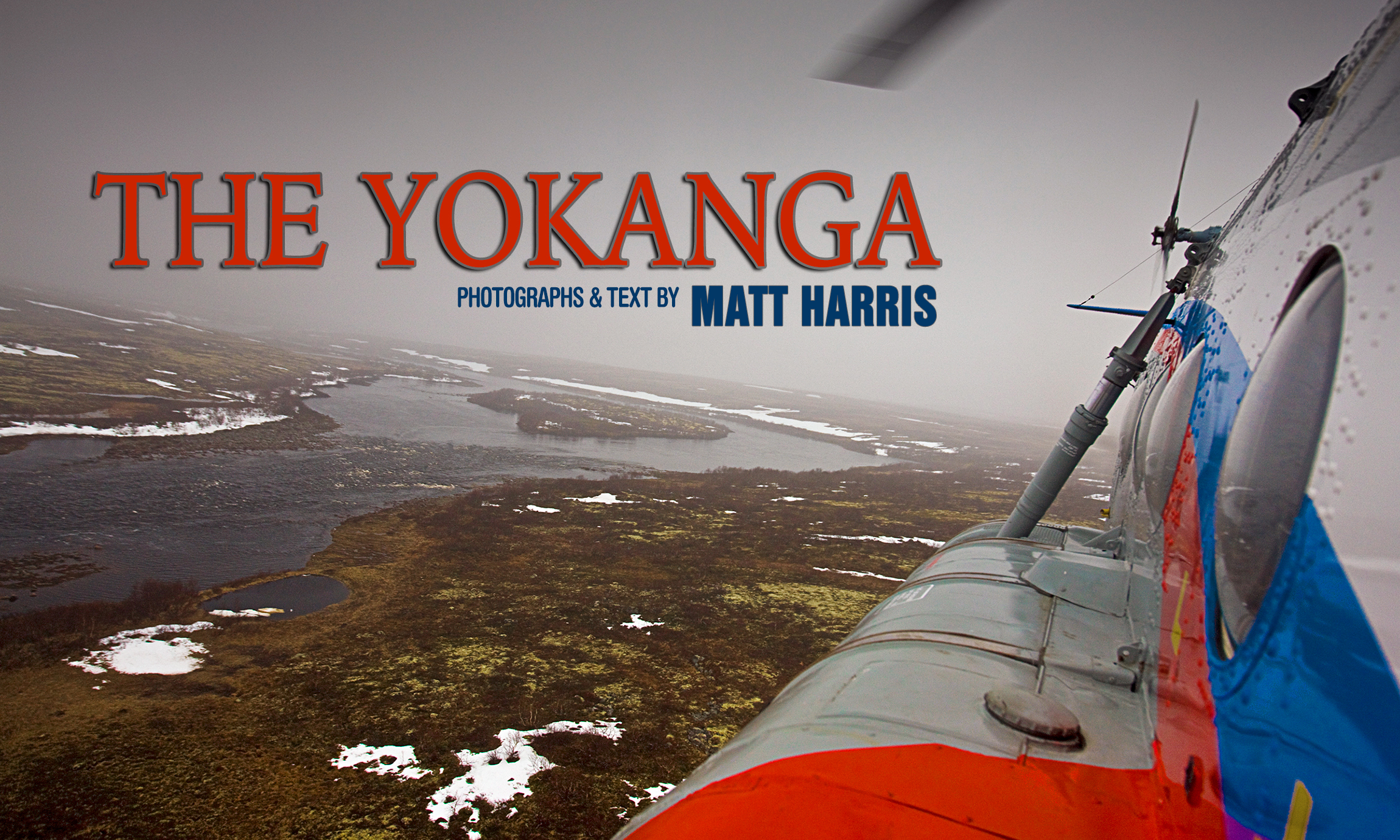

However, for me at least, that grab – that savage, primal grab – from a big Atlantic salmon, way out in the icy currents of a big, brawling river is singularly the most exciting moment that fly fishing can offer. High up on the Kola Peninsula, the vast wilderness region that straddles the arctic circle in North West Russia, an inconspicuous little stream trickles

out of Lake Alozero. In its upper reaches it meanders placidly across the flat tundra. Fed by numerous tributaries, it starts to swell in size and picks up speed as the gradient starts to steepen.

Finally, in its last few miles, the river drives down off of the table-land of the tundra, forcing its violent and unrelenting way through the craggy bedrock of the northern coastline and crashing into the Barents Sea at the god-forsaken Military Base at Gremikha Bay.

The lower section of this watercourse is a formidable maelstrom of boiling rapids and crashing chutes. This savage, uncut diamond of a river has forged a race of Atlantic salmon like no other.

This river is the Yokanga, and the salmon that run it are simply the strongest, the wildest and the most magnificent fish that I have caught anywhere in fresh water.

While I have fly fished far and wide in more than twenty countries over the last two decades, I have fished the Yokanga every year since I first visited it in 2001.

The scientists of the Russian Polar Research Institute have designated the river as having the largest strain of Atlantic salmon on the Kola Peninsula, but their dry academic pronouncement doesn’t begin to equip you for the wild, rollercoaster ride that these fish are capable of taking you on.

“The moment that I buckle myself in, grinning at my fellow veterans and feeling the big rotor of the workhorse Russian Mi8 helicopter starting to wind up on the bleak tarmac, I still get goosebumps.”

As the Jameson whisky makes the rounds, and the bleak old concrete city of Murmansk recedes into the distance, I experience a familiar thrill. This is still the most special and the most exciting day of my fly fishing year.

“What’s so special about Yokanga?”

It’s not the big, familiar home-away-from-home timber lodge on the middle river, the laughs with old friends over a delicious, rib-sticking supper or a late night-cap, or the thrill of seeing those dear old veteran guides – Vova, Sasha, Edvard, Anatoly, Big André, and the rest, year on year.

It’s not the magical white nights, wading the home pool or the notorious Lilyok confluence, while the sun briefly gutters behind the hill across from the lodge before peeping back up an hour or two later.

It’s the fish. It’s simply the fish. Those big, brutal, magnificent fish.

Until you’ve hooked one of these fish, you simply can’t understand what the fuss is all about. They are like no other salmon – like no other fish – that I’ve ever tangled with.

If you are going to tackle the salmon of this brutal river, then be prepared. Never has the maxim “Fail to prepare and prepare to fail” been more apt. If there is a chink in your armour, these fish will find it.

Fuss all you like about flies, about new rods, about the latest fly lines. But before you do, make sure that your reels are in good order, have a smooth and powerful drag, and are loaded to the hilt with at least 400 metres of well-maintained 65lb gelspun backing.

Your hooks should be sharp and ultra-strong – Ken Sawada XD1 tube doubles in size 2 and 4 are the only choice for the brutal environment of early spring. Partridge Patriot doubles are excellent for dressed flies in later weeks. Leader should be ultra-abrasion resistant Seaguar Fluorocarbon in 30lb, 35lb and 44lb Breaking Strain.

The Yokanga is heavily tannin-stained, and thus flies from the orange side of the spectrum work well. In early season, look no further than the lethal German Snaelda. Later in the season, Sunrays, Willy Gunns and Templedogs tied with similar hues work well, although the Green Highlander is a great change fly if you move a fish.

“Bring at least two 15’ ten-weight spey rods – I like to carry a six-piece version as an easily toted back-up in case of breakage.”

I also have a third rod waiting and ready on the rack back at the lodge so that I can win that evening race for the killer spot while my friend is re-rigging his set-up.

I carry two main lines – The RIO Skagit Max Long is my go-to in the high water of early season. It can throw anything from small doubles to one-inch tungsten tubes, and it means I simply don’t have to change my shooting head – it just gets EVERYTHING done. I break with orthodoxy and fish 15’ tips, and the Max will send them flying across even the widest pools of the Yokanga with ease.

In the typically lower, warmer water of mid and late season, a RIO Scandi body in 10 or 11

weight, fitted with tips from floating to Type 8 is a more elegant, more subtle way to present your fly. It will cover most eventualities, but carry the Skagit just in case you want to start lobbing a bigred frances or snaelda into the deepest, darkest pools.

Good, tough, felt soled boots and a pair of robust and leak-free chest waders are a must. A tube of UV Wader repair can be a godsend – the early season water is savagely cold.

At the very top of your packing list is a good, reliable wading stick. The Yokanga’s big, boulder-strewn pools require careful but aggressive wading and you need to be safe in what are sometimes powerful currents.

Take extreme care.

“So, once kitted out, you’re ready for the big one – or are you?”

The moment when you first hook a big Yokanga salmon is thrilling and terrifying in equal measure. Even if your gear is absolutely bullet-proof, these big chrome berserkers will find a million ways to wreck your dreams.

That moment – that big wrenching grab – can come out of nowhere, so be ready. This is it.

The moment that you have dreamt of all through the long dark winter, the long business meetings and the rain and the traffic jams and the late nights at the tying bench. It’s a moment that may only come once in your week – perhaps only once in your life – when you are suddenly attached to a true Yokanga leviathan.

As my Norwegian friend Stig Skokeng likes to say: “Don’t f@ck it up.”

The key thing is to give the fish plenty of time to take the fly before smartly lifting the rod to set the hook. Bear in mind that monofilament running line has a lot of stretch, so bang that hook in hard, especially at long range. Once the fish is on the reel, take it easy and try not to pull too hard. Treat the fight like a boxing match.

In the first few rounds, all the advantages are with the fish. In the heavy currents of early season, the fish can disappear downstream in a few short seconds, and people are routinely spooled on the river.

In order to avoid this, the first thing you should do is get out of the river and try – if possible – to get downstream of the fish, so that the fish is now fighting both you and the current.

Pull downstream to encourage the fish to run upstream, further increasing your advantage. Don’t panic your adversary by pulling really hard – the fish may freak out and just head back to the sea. Instead, just let the fish believe that it is in charge. If you are lucky, it may calm down and just go back to its lie. Slowly work on the fish, applying gentle but unremitting pressure, and backing off the drag so that if the fish runs downstream, it doesn’t fight against heavy pressure.

As the fish starts to tire, gradually increase the pressure, but always be ready for the fish to run downstream. I have chased five different Yokanga fish for well over a kilometre, and I’ve landed two of them.

Look for slack water – you will have a huge advantage if you can find a back-eddy or bay in which to fight out the end-game. When the fish starts to really tire, draw it into the slack, where the lack of oxygen will really affect its ability to fight.

The lack of powerful current also allows you to net the fish more efficiently and safely.

Don’t be in a rush, and wait until the fish is properly beaten before you draw it into your guide and his waiting net.

I’ll say it again. I’ve been lucky. I’ve fished Yokanga for nearly two decades, and I’ve caught some stunning fish.

Yet the real behemoth – the forty – the one that we all dream of, has so far eluded me.

I’ve chased fish down the craggy boulder-fields, through icy side-streams and long, slippery rapids, my throat dry and any number of wild prayers swirling in my head.

I’ve felt that awful gutless mechanical trance after 90 minutes of chasing the fish down the river – the fish that I’ve dreamt of all my adult life – has suddenly raced around a big boulder midstream and broken my backing and my heart.

Get over it. Tie on a new fly – and a new fly-line if necessary – and wade back in.

On Yokanga, each and every cast could see that impossible, fabulous silver leviathan come thrashing wildly out of your dreams and into your guide’s cavernous landing net.

This summer, I experienced that feeling. I landed a magnificent 37-pound fish, my biggest yet from the river. It’s no exaggeration to say, as a passionate salmon fisherman, I will carry that moment with me as long as I live.

MATT HARRIS

Contributed By

Matt Harris

Matt Harris has fished the Yokanga every year for nearly two decades and was recently appointed an ambassador for Yokanga Lodge. He hosts weeks throughout the season, and can advise on all aspects of fishing this special river.

If you are interested in fishing Yokanga, get in touch with Matt at [email protected] or via Matt’s website at: www.mattharrisflyfishing.com.